Effects of Climate Change on the invasive Lionfish: Pterois volitans and Pterois miles

By Patricia Albano, SRC intern

Across the globe, marine environments face anthropogenic stressors that threaten their continued survival. Throughout the world’s oceans, a colorful variety of marine communities exist, each with their own native flora and fauna and unique interspecific and intraspecific interactions. When the balance of these ecosystems is altered, negative ecological impacts can follow. The introduction of invasive species into marine communities in which they do not belong can have significant and long-lasting effects on the health, balance, and abundance of native species in the environment (Carlton, 2000). A well-known culprit, the Indo-Pacific lionfish, Pterois volitans or Pterois miles, has invaded the Western Atlantic ocean where it voraciously preys upon native species and reproduces in abundance. Via the reports of various divers, researchers, and fishing operations, it has been determined that the lionfish distribution along the east coast of North America may span from the Florida Keys to Cape Hatteras, North Carolina and include water depths up to 100m (Whitfield et al., 2002). For such invasive species to thrive in non-native ecosystems, several environmental factors come into play, one of the most notable being climate change. It has already been noted that increasing global ocean temperatures can predictably influence the growth and reproduction of marine fish and invertebrates (Brown et al., 2004). Consequently, increased growth and reproduction rates can directly impact population increases. For native species, this would be less of a concern; however, with the destructive influence that invasive species propose, it has become an epidemic. All of this considered, it can be concluded that climate change likely propagates invasions rather than halting them, especially in the case of lionfish (Côté and Green, 2012).

Indo-Pacific Lionfish: Pterois volitans. Popular in the aquarium trade for their superfluous body shape and coloration, Indo-Pacific lionfish pose a threat to invaded areas due to their voracious appetite and extreme reproductive capacity. Image source: Wikimedia Commons

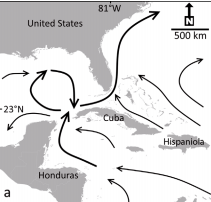

After being introduced into coastal Florida waters in the 1980s through the aquarium trade, the Indo-Pacific lionfish has taken over the entire Caribbean basin and much of the Western Atlantic, infiltrating coral reefs, seagrass beds, and mangrove communities. It is predicted that lionfish life-history and behavior are intrinsically temperature-dependent based on observations of their reproduction and diet (Côté and Green, 2012). In a study concerning the effects of warming temperature on lionfish pelagic larval duration and dispersal and predation rate, it was found that increased temperatures set the perfect stage for an invasion to thrive. Due to their generalist diet, ability to expand their introduced range, and high fecundity, lionfish will continue to remain a threat in the Western Atlantic (Côté and Green, 2012). Increased temperature was predicted to drive the present imbalance between prey consumption and production rates, resulting in the lionfish having the upper hand in the ordeal. As oceans continue to warm, the lionfish will be able to expand its range to areas that are currently too cold for their inhabitation, specifically as the 10°C isotherm expands north and south in both of the hemispheres (Morris and Whitfield, 2009; Côté and Green, 2012). Finally, lionfish spend less time in the pelagic larval stage with increased ocean temperature, leading to growth of populations as temperatures continue to rise (Côté and Green, 2012).

Temperature anomaly of average global sea surface temperature from 1880-2015. This increased warming trend is predicted to continue and proceed to facilitate the lionfish invasion into regions further north and south of the equator. Figure source: United States Environmental Protection Agency (https://www.epa.gov/climate-indicators/climate-change-indicators-sea-surface-temperature)

According to the National Ocean and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), average global sea surface temperature has risen at an average rate of 0.13°F per decade since 1901 (Figure 1). Although this may seem like an insignificant increase, at this rate, global average sea surface temperature is predicted to hover around a 1°F anomaly from historical average by the year 2020, and steadily increase from there. With these elevated sea water temperatures, lionfish will continue to capitalize on climate change if this pattern is not halted. For the time being, one of the only limiting factors that the lionfish invasion faces is the fish’s intolerance to minimum water temperatures of some of its extended ranges away from the equator during the winter time (Kimball et al., 2004). However, this temperature anomaly pattern could facilitate expansion of the depth and latitude range of these invaders. In a study conducted on thermal tolerance and potential distribution of lionfish, it was found that the mean chronic lethal temperature for lionfish was 10°C and mean temperature for them to cease feeding was 16.1°C (Kimball et al., 2004). The average temperature for Florida waters during the winter time is 22°C and about 10°C at the northern limit that lionfish range, Cape Hatteras. These average water temperatures and this study show that as water temperatures continue to increase, the range of lionfish will continue to expand.

Overall, it can be deduced that climate change proposes a large threat to marine communities, especially where invasive species are concerned. As temperatures continue to rise above the norm, lionfish will extend their invasion further along the Western Atlantic.

Works Cited

Brown JH, Gillooly JF, Allen AP, Savage VM, West GB, 2004. Toward a metabolic theory of ecology. Ecology 85: 1771–1789.

Carlton JT, 2000. Global change and biological invasions in the oceans. In: Mooney A, Hobbs RJ ed. Invasive Species in a Changing World. Covelo, Calif ornia: Island Press, 31–53.

Côté IM, Green SJ (2012) Potential effects of climate change on a marine invasion: The importance of current context. Curr Zool 58:1–8

Kimball ME, Miller JM, Whitfield PE, Hare JA (2004) Thermal tolerance and potential distribution of invasive lionfish (Pterois volitans/miles complex) on the east coast of the United States. Marine Ecology Progress Series 283:269–278

Morris JAJ, Whitfield PE, 2009. Biology, ecology, control and management of the invasive I ndo-Pacific lionfish: An updated integrated assessment. NOA A Technical Memorandum NOS NCCOS 99.

Whitfield PE, Gardner T, Vives SP, Gilligan MR, Courtenay WR, Jr., Ray GC, Hare JA (2002) Biological invasion of the Indo-Pacific lionfish Pterois volitans along the Atlantic coast of North America. Mar Ecol Prog Ser 235:289–297