How Marine Reserves Can Help Preserve Ecosystems by Reducing Bycatch

By Jess Daly, SRC Intern

One of the greatest environmental impacts of industrial fisheries is the accidental removal of species in bycatch. Many fisheries have a single target species that they look to catch when they fish. Any other species that pull up in their nets or on their lines are known as bycatch. These fish are often simply discarded since the fisherman will not make money off them, even though they may be of great importance to the ecosystem. Bottom trawling is one type of fishing that involves dropping weighted nets to the bottom of the ocean and dragging them along the sea floor. Nearly 23% of fisheries use trawl nets as their primary fishing method, which is criticized both for its very high bycatch percentage (anything on or near the bottom will be pulled up in the net) as well as the destruction of corals colonies from the weights being dragged across them (Van Denderen et al, 2016). Other kinds of fishing nets, such as midwater trawls and driftnets, also typically have high bycatch percentages.

Figure 1: This illustration shows what a bottom trawl fishing net looks like as well as how it works. Source: Mr. Bijou, Blogspot

Bycatch is a serious problem, but not one that is easy to solve because of limitations of fishing equipment and the inherent difficulty of trying to fish for a single species. Traditional methods of reducing bycatch, such as limiting the total number of fish that can be taken, can be difficult to enforce and are economically costly for the fisherman (Hastings et al, 2017). Using specialized fishing gear is a second potential method, but can also be quite expensive and is not always effective. Recently, the concept of using marine reserves as a tool to help reduce bycatch has begun to gather interest. Marine reserves are areas that are designated “no-take,” meaning that nothing can be removed from the area. Fishing, bottom trawling, and taking of shells are among the activities that are not allowed inside the reserve. They are usually areas that are of great importance to fish species for a specific reason, such as a mating grounds or nursery. It has been shown in multiple studies that marine reserves cause increases in fish populations and can help depleted species to recover their numbers (Mumby and Harborne, 2011). Large female fish are exactly the type that fisherman hope to catch, so without protection they are fished out quickly and the population declines because they are not reproducing. Inside a no-take area, however, female fish can grow larger and thus produce larger, healthier offspring. The population increases and eventually flourishes, maintaining the health of the ecosystem and the fisheries’ profits simultaneously.

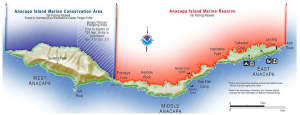

Figure 2: The waters off Anacapa Island, California are one example of a marine reserve, or “no-take zone”. The map shows the reserve area in red. Source: Matt Holly, National Parks Service

In some fisheries the primary bycatch species, also known as the weak stock, are slow to mature, have long lifespans, and produce fewer offspring than target species. Some fishing practices intended to maximize target species catch may decimate the weak stock and wreak ecological havoc (Hastings et al, 2017). A 2017 study conducted by Drs. Hastings, Gaines, and Costello used extensive mathematical modeling to examine the potential effects of marine reserves on fisheries. They found that in every case where the weak stock was a species with a longer life expectancy and lower reproduction rate than the target species, marine reserves increased target species yield more than other management methods. They also showed that creating no-take zones specifically designed to protect bycatch species did not decrease the maximum yield of the target species (Hastings et al, 2017).

In the first case the marine reserves increase target species yield because there is no limit on specific catch numbers, and also because they protect areas of great importance to the fish. If this area is a breeding ground or nursery, this protection results in more offspring being produced and then going on to survive to adulthood. If there are more fish in the water, more of them can be caught without damaging the population or the ecosystem. In the second case, where the marine reserve is specifically tailored to protect the bycatch species, the target species catch does not decrease significantly because the fish share a habitat. Even if the protected area is not of special importance to the target species, the fish still live in that area. If they cannot be caught inside the reserve, their numbers can increase and are able to offset extra fish that might be taken from outside the reserve.

While it may seem that completely prohibiting fishing in high-production areas would lead to decreases in fisheries profits, there is strong evidence that marine reserves effectively and cost-efficiently maintain profit margins while mitigating the economical damage of many fishing practices. By protecting bycatch species and limiting the number of unwanted fish that are removed from the ocean, ecosystems can better withstand fishing pressures and better recover from past overfishing trauma.

Works Cited

Hastings, Alan, et al. “Marine Reserves Solve an Important Bycatch Problem in Fisheries.” Proceesings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, vol. 114, no. 34, 22 Aug. 2017, pp. 8927–8934, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5576807/.

Mumby, Peter J., and Alastair R. Harborne. “Marine Reserves Enhance the Recovery of Corals on Caribbean Reefs.” PLOS ONE, Public Library of Science, 11 Jan. 2010, journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371%2Fjournal.pone.0008657.

Van Denderen, Pieter Daniël, et al. “Using Marine Reserves to Manage Impact of Bottom Trawl Fisheries Requires Consideration of Benthic Food-Web Interactions.” Ecological Applications, vol. 26, no. 7, 2 Sept. 2016, orbit.dtu.dk/ws/files/123769828/Postprint.pdf.

Holly, Matt. “Anacapa Island Map.” Wikimedia Commons, National Parks Service, 25 Feb. 2016, commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:NPS_anacapa-island-map.jpg.

“Mr. Bijou”. “How Bottom Trawling Works.” Oceans Become Deserts, Blogspot, 10 Jan. 2006, misterbijou.blogspot.com/2006/01/.