Ballast Water Management and Its Implications Regarding Invasive Species Introduction

By Casey Dresbach, SRC intern

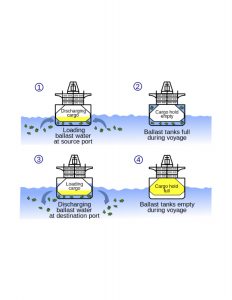

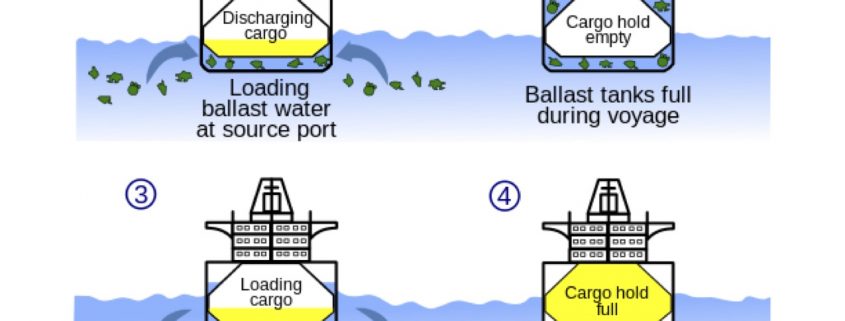

Ballast water, either fresh or salt water, and sometimes containing sediments, are held in tanks and cargo holds of ships to increase stability and maneuverability during transit. It’s advantageous in its means to stabilize, increase propeller immersion to improve steering, and to control trim and draft. Often times, cons outweigh the pros in the ballast water process. In regards to the marine ecosystem, ballast water discharge contains many plants, animals, viruses, and microorganisms some of which can be invasive or exotic species that can lead to detrimental ecological and economical effects, as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Depiction of how Ballast Water Management can instigate water pollution of the seas from untreated ballast water discharges

Invasive species are a major threat to biodiversity in the marine ecosystem. Once integrated, they become predators, parasites, and diseases of native organisms. Unfortunately, many of these nonindigenous species (NIS) are spreading across the seaboard. These invasive species are making their way into ballast water of ships globally. These ships are picking up water in one location, carrying their said cargo across the seas (ranging from far to close distances), and then discharging that water at their acquired destination. By doing so, the ships transport a subset of native species from one ecosystem into another, to which they may not be native.

In the 15th century, the shipping industry expanded exponentially and led to an increase in the number of vessels. By the 18th century, the expansion was furthered in steam technology, with the addition of more complex vessels that required more stability efforts. Ballast water was issued to these vessels, consequently increasing opportunities for nonindigenous species to spread.

At the global scale, initial efforts have been underway in the past twenty five years to control unwanted nonindigenous species with the Nonindigenous Aquatic Nuisance Prevention and Control Act of 1990, and later the National Invasive Species Act of 1996. Such policy instigation focused on aspects from mid-ocean ballast exchange to quantitative standards of permitted organism density upon ballast water discharge. Among all, there have been exemptions or exceptions to the proposed policies, including crude oil tankers engaged in coastwise trade.

A study in Alaska was initiated in regards to questionable effects of exemptions. The study focused on determining the “effectiveness of existing shore-side ballast water facilities used by crude oil tankers in the coastwise trade off Alaska.” The results indicated a high risk of NIS transport from ballast water discharged in Prince William Sound, Alaska. Much of the ballast water was discharged along intra-coastal shipping routes that originate on the Pacific Coast of North America from invaded source ports. Prince William’s largest port, Valdez, may serve as a designated area for the secondary transfer of nonindigenous species.

The initial BWM policy was not enforced it was voluntary; the nonbinding guidelines were insufficient and continued invasion and warranted stronger action. With that in mind, the initial efforts of BWM were more of a reactionary process because the invasions had since occurred. On November 21, 2001, the United States Coast Guard (USCG) published its final ruling. Since participation in the voluntary program was insufficient to the success of the program; BWM was now going to become mandatory. With this mandate, vessels (other than those exempted: crude oil tankers engaged in coastwise trade, Department of Defense of USCG vessels, and vessels operating within one USCG Captain of the Port Zone) would be fined or issued a monetary civil penalty up to $35,000.

With growing concern, the IMO (International Marine Organization) developed “The International Convention for the Control and Management of Ships Ballast Water and Sediments,” in 2004, to further protect the marine ecosystem from the transport of detrimental nonindigenous species in ballast water carried by vessels.

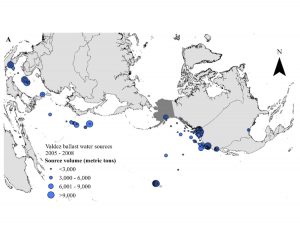

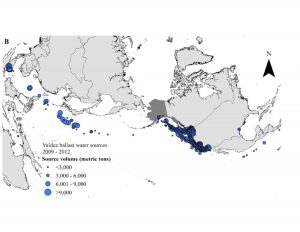

In 2005 policy initiatives were furthered, and BWM was mandatory for all vessels in the United States, with the same exemptions as before. By 2008, management and recordkeeping requirements went into place with the hopes of decreasing these risks. However, many of those exempted from the BWM such as the crude oil tanker traffic had their transports undocumented and under-reported. As seen in Figures 2 and 3, exemptions from management have negated these efforts to reduce invasion risk. Studies found a 440% increase in ballast water discharge to Alaska in the following year. In a review of ballast water discharge to Alaska (Danielle E. Verna, Bradley P. Harris), a suggestion was made that a precautionary approach to exemptions was of dire need, as well as consistent assessments of the vessels expeditions to reduce the risks of increased invasion.

Figure 2A. Valdez, Alaska water ballast water sources from 2005-2008.

Figure 2B. Valdez, Alaska water ballast water sources from 2009-2012 shows an exponential increase in source volume, primarily due to consequence of exempting a sector.

The inclusion of intra-coastal vessel traffic as well as a better understanding of the NIS risks at stake may reduce the risk of further invasions. The most beneficial impact to the Alaskan industry practices was when BWM became mandatory to all vessels. However, the exemption factor is what threatened to negate the initiative. With continued assessment of vessel behavior and transport as well as documentation and data recordings can help trace back to where this exemption may take their turn in increasing the risk of NIS introduction. Moving forward, policy makers will continue to do their job, but further education among communities will only benefit their obligatory feats.

Resources

International Marine Organization. (n.d.). Ballast Water Management. Retrieved October 24, 2016, from IMO : http://www.imo.org/en/OurWork/Environment/BallastWaterManagement/Pages/Default.aspx

MaxxL, & Hartmann, T. (2014, June 24). Ballast Water. Retrieved October 24, 2016, from Wikimedia Commons: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Ballast_water_en.svg

Reece, J. B., Urry, L. A., Cain, M. L., Wasserman, S. A., & Minorsky, P. V. (2014). Campbell Biology . Boston: Pearson.

Verna, D. E., & Harris, B. P. (11, April 2016). Review of Ballast Water Management Policy and Associated Implications for Alaska. Elsevier Journal .

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!