Threats to Sea Otters

by Daniela Escontrela, RJD intern

Sea otters are a very charismatic species due to their very cute and cuddly appearance; however, sea otters are quite interesting animals for many reasons. For one sea otters lack a blubber layer like many other marine mammals. To make up for this, they have the thickets fur of any animal coming in at one million hairs per square inch, 800 million total (compare that to humans who have a mere 100,000 hairs on their entire heads) (Cohn 1998). Otters are also the only marine animal known to use tools. They place a rock on its belly while they float on their back and strike mussels and clams against them to open them. They will consume one quarter of their body weight in food and their high metabolic system quickly turns that food into heat energy. Sea otters are slow reproducers, having one pup every two years (Waldichuk 1990). Additionally, sea otters were one of the last marine mammals to adapt to life in the ocean and they are the second smallest marine mammal (Cohn 1998). Sea otters spend most of their time at sea; in fact when sleeping they will wrap themselves in kelp to keep from drifting away with the current (Waldichuk 1990).

Figure 1. A sea otter at the Monterrey Bay Aquarium laying on its back, a characteristic pose of this animal (Cohn 1998).

However, as cute and charismatic as these animals are, they have suffered great tragedy. Sea otters in North America were first discovered in 1742 by Vitus Bering from Russia who got shipwrecked in the Bring Sea (Waldichuk 1990). At the time, otters ranged from Japan and the Kamchatka Peninsula across the Commander and Aleutian islands to Alaska and down the west coast of North America to Baja California. The shipwrecked survivors first used the otters for food but soon discovered how valuable the coats could be. When word got back to Russia, people from all over the world would make their way to the west coast of North America to hunt the animals for their fur (Cohn 1998). These animals were hunted all throughout the 18th and 19th century and estimates are that 400,000 were killed in that time. By the 1900s, only a few dozen remained in California with a few handfuls in other regions (Lafferty and Tinker 2014). In 1911 the animals were saved from extinction when Canada, Russia, Japan and the USA signed a treaty, called the International Fur Treaty, to stop killing them, at which point only 1000-2000 remained in the wild (Waldichuk 1990). In addition, the sea otters were listed as “threatened” under the endangered species act, the marine mammal protection act listed them as depleted and California as a “fully protected mammal”; they are also protected under Russian law (Cohn 1998).

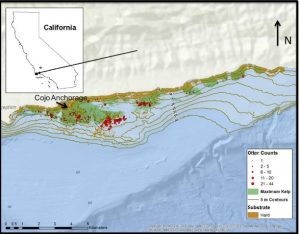

In the recovery process sea otters have been relocated from areas where they are abundant to areas where they are depleted. In the past couple of decades numbers have increased to ~150,000 in Alaska and the Aleutian islands, 17,000-18,000 in Russia and northern Japan, 1000 in British Columbia, 2000 in California and 500 in Washington (Cohn 1998). Even though it seems sea otters are out of danger that is far from the truth. Although they are no longer exploited for their fur, there exist other threats. For one, sea otters are highly susceptible to oil spills. Sea otters spend a lot of time grooming their fur and as such they are highly vulnerable to ingestion if coated in oil. When the Exxon Valdez oil spill occurred in the Prince William Sound in Alaska, 42 million liters of oil were released into the water killing at least 450 sea otters. Many suffered from liver damage due to ingestion of oil during grooming. In addition, the fur is also susceptible to oil as the underfur layer, which usually stays dry, loses the insulation quality and animals end up dying of pneumonia. Although a large oil spill hasn’t occurred in California, many conservationists want the introduction of sea otters into southern California, where they were once abundant, in the case of a spill (Waldichuk 1990). However, expansion into southern California has been sporadic. Sea otters prefer to stay near shore and at the moment, sea otter abundance in central California may be at its carrying capacity limited by food and shelter. If southern California can hold the same density of otters as central California then sea otter populations could rise to 16,000; clearly range expansion is key to further population recovery. In an effort to direct an expansion of sea otters while minimizing competition with fishermen, US Fish and Wildlife created a “no-otter” management zone south of Point Conception (which divides central from southern California). For many years, if otters were found to the south of this they would be relocated to central California. However, in 1998 a group of 93 males was seen south of Point Conception, a group too large to relocate. Since then patterns of migration have been observed for the otters. Males will travel south from winter to spring in search of resources then return to the center ranger after females wean their pups and come into estrous. These groups of non-territorial males at the range margins colonize adjacent open habitat to exploit abundant resources, often in response to increasing prey competition the previous neighboring habitat they occupied. If these males stay in this territory for 5 to 10 years, other females and pups will begin to arrive. At this point there is a demographic transition from male colony to mix sexed groups. Males will then establish territories which forces non-territorial males to move again to new territory and to start the cycle again. This cycle makes growth and expansion slow and intermittent. In December 2012 US Fish and Wildlife Service determined the California translocation program a failure and ended it, halting enforcement of the “no-otter” management zone (Lafferty and Tinker 2014). If this pattern of southern expansion continues, sea otters could become more resilient to oil spills if they were to occur since the population would be spread out rather than clustered in central California.

Figure 2. Map of sea otter counts (red circles) and maximum kelp coverage south of Point Conception (Lafferty and Tinker 2014).

This migration of sea otters towards southern California is a step in the right direction; however, other threats still abound especially in California were growth rates lag behind at 5% per year, compared to 15-20% per year for Washington. This slow growth rate may be due to the high mortality rate of pups (40%) which is far higher than in other places. Previously, many males were dying from gill nets since males rest and feed further from shore where they are more susceptible to encounter these nets; luckily gillnets have been band. Natural threats include predation from sharks, especially in the North, and from killer whales. Another major threat is a parasitic worm that hits juveniles and pups; this worm normally infests seabirds. A veterinary pathologist that examined 250 corpses found that 40% had died from this infectious disease. Sea otters are also susceptible to San Joaquin valley fever, a fungal disease usually seen in people living in arid areas. It is proposed that the disease finds its way to sea through airborne dust (Cohn 1998). If this wasn’t enough, another disease was discovered to also cause mortality in otters called Toxoplasma gondii. This single celled protozoan is pathogenic and causes protozoal encephalitis in otters. This is a deadly brain infection that causes tremors in the front legs and loss of muscle action. This prevents the animal from diving for food and grooming (a healthy sea otter spends one third of its day grooming). T. gondii comes from cats who excrete the protozoan’s eggs in their feces. The eggs can survive up to 18 months and due to rain off it makes its way to the ocean. As of 2003, out of 1000 dead sea otters that had washed up along the California coastline, 62% of them had died from the Protozoan infection (McLaughlin 2003).

The threats abound to sea otters who happen to be a keystone species. A keystone species is a plant or animal that plays a crucial role in the way an ecosystem functions. Without a keystone species, the ecosystem would be dramatically different or cease to exist altogether. Sea otters prefer coastal marine habitats dominated by kelp stands where they can find one of their staple food items, sea urchins. Heavy overgrazing by sea urchins on kelp forests can deplete them. However, if sea otters are present they can keep urchin levels low which prevents overgrazing (William 1988). In a study after the Exxon Valdez oil spill it was found that oiled areas where there were few sea otters had 1.52 urchins per 100 square meters versus 0.17 urchins per 100 square meters in non-oiled areas were otters were more abundant. These areas with higher densities of urchins experienced overgrazing and depletion of kelp forests. In fact some scientists believe that North American kelp evolved with otters. Kelp in Australian waters produce toxins to ward off urchins whereas kelp in North America do not produce this toxin since it did not need chemical defenses due to the presence of otters. It is important to keep sea otters around as they can help modify environments such as kelp forests which provide shelter and food for countless fish, shellfish, urchins and marine mammals and birds (Cohn 1998). It is of extreme importance that more research go into sea otter conservation to study things such as the diseases that are killing them and to come up with recovery plans in the case of an oil spill; arguably these are two of the biggest threats they face that we must confront in the near future if we don’t want to drive them to extinction.

Works Cited:

Jeffrey, P Cohn. “Understanding Sea Otters.” BioScience 48.3 (1998): 151-155.

Lafferty, Kevin D and Tim M Tinker. “Sea otters are recolonizing southern California in fits and starts.” Ecosphere 5.5 (2014): 1-11.

McLaughlin, Sabrina. “The Otter Limits.” Current Science 88.14 (2003): 4-5.

Waldichuk, M. “Sea Otters and Oil Pollution.” Marine Pollution Bulletin 21.1 (1990): 10-15.

William, Booth. “The Otter-Urchin-Kelp Scenario.” Science 241.4862 (1988): 157.