Age-specific foraging performance and reproduction in tool-using wild bottlenose dolphins

By Elana Rusnak, SRC Intern

Foraging (searching for food) is a skill that animals use to provide energy for survival, growth, and reproduction. In many animals, these skills are fully developed before reproductive age, maximizing the energy put into reproduction when sexual maturity is reached. However, female bottlenose dolphins (Tursiops aduncus) in Shark Bay, Western Australia, learn a unique foraging behavior from their mothers during development, yet continue to hone their skills long after reaching sexual maturity (at around 10 years). This complex foraging behavior includes the use of sponges as tools; the dolphin will forage for a sponge and then “wear” it on their beaks while searching for prey on the seafloor (the benthic zone). The sponge provides protection from sharp rock and shell debris, and allows “spongers” access to a unique food source. Other “non-sponger” dolphins eat fish and other prey in the water column, otherwise known as the pelagic zone. Sponge foraging (sponging) is a complex skill that takes years to develop. Researchers question why such an important skill would not be developed fully before reproductive age.

A female bottlenose dolphin with a marine sponge tool in Shark Bay, Western Australia.

A study published by Patterson et al. in 2016 attempts to explore age-related changes in foraging performance. They examined three aspects of foraging efficiency: the ratio of time spent acquiring sponges to time spent foraging, the time spent foraging per tool (sponge), and the time spent traveling per tool. Their hypothesis estimated that maximum efficiency should result from shorter times acquiring the tool and longer times spent using them. They then examined how age-related changes in foraging performance relate to changes in female reproduction.

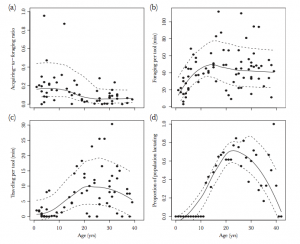

The data was collected between 1989 and 2012 and covered roughly 1800 individuals. The three stages of behavior (acquiring sponge, using sponge, travelling with sponge) were classified by the researchers and observed in the wild. Analysis included various statistical tests that modeled the three variables and percent of the population that was reproductively mature against age. It was found that sponge-acquiring behavior makes up a small percentage of an individual’s activity budget (as predicted before the study). As can be seen in Figure 2, until the age of 23.72 years, dolphins gradually learned to spend less time acquiring the sponge and more time using it (a). Until the age of 19.50 years, the time spent foraging per tool gradually increased and then remained stable (b). The model also shows that there was a gradual increase in the time spent traveling per tool as age increased up to 23.34 years of age (c). Finally, the model showed that peak foraging ability improved until roughly midlife (20-25 years), which is well after the onset of sexual maturity. This can be seen by comparing (a), (b), and (c) with (d), which shows age vs. percent of the population at different stages of reproduction.

Age specific foraging and lactation. This shows the relationship between age and the three studied variables, as well as its relationship with reproductively active females.

What did the researchers conclude?

Overall, the data suggest that dolphins continue to improve performance in their tool-use foraging techniques long after they reach sexual and physical maturity. Females increased their foraging efficiency with age by decreasing acquisition time and increasing foraging time. By midlife, it can be concluded that they have learnt how to find the most ideal sponge for foraging, as well as figured out the best way to use it in order to avoid needing replacement. They also learn that reusing a good tool is important, and therefore are more willing to travel with it to avoid needing to find a replacement.

The most important conclusion taken from the data is that while dolphins reach sexual maturity at around 10 years of age, their peak reproductive age coincides with the peak foraging ability (20-25 years of age). It may be that it is advantageous for an individual to reach sexual maturity as soon as their foraging skills are good enough, and then continue to improve efficiency with age in order to increase reproduction. This behavior is seen in other animals, such as chimpanzees, capuchin monkeys, and sea otters. This study proves that we should not be surprised that foraging expertise after reaching adulthood has positive fitness consequences, and allows for higher rates of reproduction.

Reference

Patterson, E. M., Krzyszczyk, E., Mann, J. (2016). Age-specific foraging performance and reproduction in tool-using wild bottlenose dolphins. Behavioral Ecology, 401-410. Retrieved October 20, 2016.