ICZM in Cuba: Challenges and Opportunities in a Changing Economic Conext

By Andriana Fragola, SRC Intern

This paper discusses the problems and shortcomings hindering proper functioning of Integrated Coastal Zone Management (ICZM) initiatives in Cuba. ICZM began in Cuba in 1992 after the Earth Summit meeting. However, planning documents have not taken the structure of the Cuban government into account, making it difficult to implement this new management strategy.

Enhanced environmental policies were established in Cuba in the 1990s, focusing on sustainable energy, environment and socio-economic development. To manage more sustainable development, the Cuban government created the Ministry of Science, Technology and Environment (CITMA), and the National Environmental Strategy (Gerhartz-Abraham 2016). Later, in 2000, the Coastal Zone Management Decree Law 212 became the major source of regulation for coastal ecosystems including wetlands, mangroves and coral reefs (Gerhartz-Abraham 2016).

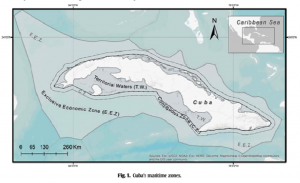

Cuba’s maritime zones

Installing ICZM in Cuba is crucial because it has exceptional biodiversity and is the largest island nation in the Caribbean. Cuba’s ocean accounts for about 48% of its jurisdictional area, and encompasses about 7% of the world’s total coral reefs (Gerhartz-Abraham 2016). There are many estuarine habitats such as seagrasses and mangroves which act as a refuge for multiple organisms during their juvenile growth periods. Cuba also receives many economic benefits from these ecosystems through medicine, fishing, tourism, and a source of food (Gerhartz-Abraham 2016).

The National Environmental Strategy concluded that soil erosion, deforestation, pollution of inland coastal waters, loss of biodiversity, and habitat degradation are the main problems the Cuban marine ecosystems face (Gerhartz-Abraham 2016). Fishing is another very important issue the Cuban reefs are currently stressed from – through overexploitation of fish, habitat damage from fishing gear, and bycatch (non-target species caught – and usually killed – during fishing).

When examining the Coastal Zone Management Decree Law 212 and enforcement of it’s regulations, one of the problems facing Cuba is that the document never explicitly details how to implement these environmental plans specifically for Cuba’s circumstances. There is also a lack of resources in Cuba to incorporate these management policies, as well as an absence of a systematic approach in the establishment and incorporation of new legislation (Gerhartz-Abraham 2016). These gaps and inconsistencies between government and political action greatly hinder the Cuban government’s ability to establish these protocols. Without addressing these issues, it will be challenging for Cuba to establish effective coastal zone management.

Coral reefs along Cuba’s coast (Montaigne, F. 2015)

In an effort to mitigate these conflicts, workshops with members of the Cuban government, coastal community members and ICZM experts have been held, making recommendations of ways to make these new regulations work, and assessing key indicators to assess how effective the plans have been (Gerhartz-Abraham 2016). There is also encouragement for local stakeholders to take part in the decision-making and development, as well as an to integrate across levels of government, creating cooperation, transparency and co-management (Gerhartz-Abraham 2016). If effective changes are made after addressing these main issues, the Cuban government will be able to protect their coastal ecosystems allowing them and their economy to synergistically thrive.

References

Gerhartz-Abraham, Adrian, Lucia M. Fanning, and Jorge Angulo-Valdes. “ICZM in Cuba: Challenges and opportunities in a changing economic context.” Marine Policy 73 (2016): 69-76.

http://e360.yale.edu/slideshow/along_cubas_coast_the_last_best_coral_reefs_in_the_caribbean_thrive/426/1/