Atlantic Bluefin Tuna Fisheries: A Case of Mismanagement

By Hanover Matz, RJD Intern

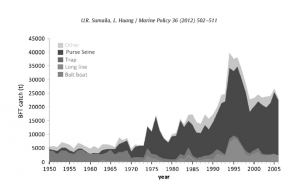

While many fisheries around the world are currently being devastated by the overwhelming power and efficiency of modern fishing fleets, the Atlantic bluefin tuna fishery of the Atlantic and Mediterranean is one that has come to the forefront of marine conservation as an example of mismanagement and overexploitation. The bluefin tuna fishery in the Atlantic has traditionally been divided between the west Atlantic and the east Atlantic and Mediterranean stocks, with disagreements over the divisions of distinct populations (Sumaila and Huang 2012). Figure 1 shows the distribution of bluefin tuna in the Atlantic, with major spawning grounds (dark gray spotted areas) and migration routes (arrows). Tuna fishing in the Mediterranean can be traced back to ancient times, with hand lining and seine fishing practiced by peoples as early as the Phoenicians and the Romans. Fishing practices expanded into trap fishing and beach seine nets between the 16th and 19th centuries, and eventually were replaced by the modern industrial seine and longline fleets of the 20th century (Fromentin and Powers 2005). It is during the late 20th century that major changes in the total catches of bluefin tuna occurred.

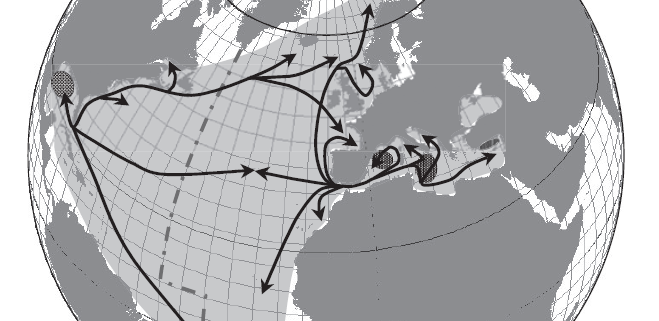

Catch data from the 1970s onward shows an increase in total catch beginning in the 1990s. Figure 2 shows bluefin tuna catches in the Atlantic from 1950 based on gear type. Bluefin tuna catches rose from levels between 5,000 to 8,000 tons in the 1970s to 40,000 tons in 1995. The International Commission for the Conservation of Atlantic Tunas (ICCAT) was established in 1969 to oversee the management of bluefin tuna, but this management has faced several issues with regards to limiting the overexploitation of tuna stocks (Sumaila and Huang 2012). One significant error on the part of ICCAT was the setting of Total Allowable Catches (TAC) above the limits suggested by advisory scientific bodies. Fromentin et al. (2014) describe the various problems that have plagued the management of bluefin tuna by ICCAT. Along with a disregard for recommended scientific limits, tuna stocks have been overfished due to the frequency of Illegal, Unreported, and Unregulated (IUU) fishing. With bluefin tuna fishing occuring over such a large expanse of ocean in the Atlantic alone, crossing waters under the control of various nations and the high seas, it is difficult to effectively enforce management policies. The authors of the 2014 report also identify how uncertainties in stock assessment have contributed to the mismanagement of bluefin tuna.

Total catch of bluefin tuna in tons by gear type since 1950, showing significant increase since the 1990s (Sumaila and Huang 2012)

Three sources of uncertainty in bluefin tuna have contributed to difficulties in establishing management policies: uncertainity in the biology and populations of tuna, poor quality of data, and errors in the ability of models to predict tuna population dynamics. (Fromentin, Bonhommeau et al. 2014). Given the migratory nature of bluefin tuna and the expanse of ocean which they inhabit, it is difficult to conduct studies on their biology and development. Catch data has also been inaccurate in the past due to the levels of illegal and unreported fishing in the industry. Finally, uncertainties in the models used to predict population dynamics make it difficult for management bodies such as ICCAT to develop effective policies. Bluefin tuna cross the Exclusive Economic Zones (EEZs) of many different countries, contributing to further difficulties in managing fish stocks that may be subjugated to fishing regulations across multiple nations (Sumaila and Huang 2012). While a better understanding of how bluefin tuna populations may overlap and mix has been established in the past decades, more research still needs to be conducted (Fromentin and Powers 2005). Another indicator that Atlantic bluefin tuna stocks have declined is the measurement of spawning stock biomass, the portion of the stock population capable of reproducing. Data since 1970 up to 2005, including both reported and illegal, unreported, and unregulated fishing, shows a decrease in spawning stock biomass by 60% since 1974 (Sumaila and Huang 2012). This means that overfishing may not only be reducing current populations, but hindering their ability to reproduce by depleting the number of reproductive individuals.

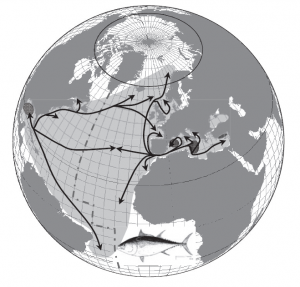

In response to increased fishing pressure on bluefin tuna stocks and decreased catches, aquaculture of tuna now occurs in several regions. Figure 3 shows current locations of tuna aquaculture. Starting with the cultivation of Atlantic bluefin tuna in Canada and Pacific bluefin tuna in Japan in the 1960s, farming of tuna has spread to the Mediterranean and Australia. However, most of this farming consists of capturing wild tuna and fattening them in pens for later harvest, while it still remains incredibly difficult and costly to rear tuna from larvae to adults. This method of catching wild tuna in seine nets and fattening them most likely does not help contribute to alleviating fishing pressures on wild stocks (Metian, Pouil et al. 2014)

Given the current level of harvesting, better management of Atlantic bluefin tuna needs to be put in place. The capacities of the purse seine net fleet and longline fleet in the Atlantic already exceed the mean productivty of bluefin tuna (Fromentin and Powers 2005). Even if there are uncertaintities in the measurements of tuna productivity, the status of tuna populations is precarious enough that it would be risky to continue the current fishing effort. Sumalia and Huang (2012) make several policy recommendations to better manage Atlantic bluefin tuna stocks. First, the total allowable catch needs to be reduced to levels as recommended by scientific research. Second, a better detection and penalty system needs to be established in order to reduce illegal fishing. Finally, the establishment of Marine Protected Areas and the listing of Atlantic bluefin tuna as endangered on the Convention for International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES) would afford tuna some protection to allow populations to recover. However, the multinational fishing effort and policy formation process of ICCAT has made it difficult to come to reasonable agreements between nations to manage tuna. To protect this valuable species, action needs to be taken to reduce the current fishing effort and total allowable catch. Better scientific research will provide more effective management tools, but the current advice being given by scientific bodies needs to be headed when establishing catch limits. If Atlantic bluefin tuna stocks are to continue to provide a valuable resource of seafood to world markets, a more sustainable fishery needs to be established.

References

- Fromentin, J.-M., S. Bonhommeau, H. Arrizabalaga and L. T. Kell (2014). “The spectre of uncertainty in management of exploited fish stocks: The illustrative case of Atlantic bluefin tuna.” Marine Policy 47: 8-14.

- Fromentin, J.-M. and J. E. Powers (2005). “Atlantic bluefin tuna: population dynamics, ecology, fisheries and management.” Fish and Fisheries 6: 281-306.

- Metian, M., S. Pouil, A. Boustany and M. Troell (2014). “Farming of Bluefin Tuna–Reconsidering Global Estimates and Sustainability Concerns.” Reviews in Fisheries Science & Aquaculture 22(3): 184-192.

- Sumaila, U. R. and L. Huang (2012). “Managing Bluefin Tuna in the Mediterranean Sea.” Marine Policy 36(2): 502-511.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!