What’s for Dinner: Seafood Fraud

by Lindsay Jennings, RJD Intern

Whether it is a grouper sandwich, a salmon filet, or a fresh sushi roll, there is a growing demand for seafood on the global menu. Over the past years, there has been an increase in seafood consumption, as an expanding list of marine life is appearing on menus at fast-food eateries, take-out dining establishments, and fine dining restaurants.

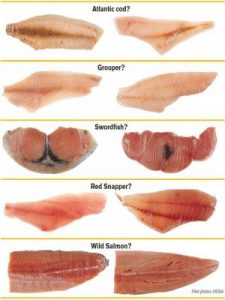

This increase in consumption, though, has given rise to a practice known as seafood mislabeling, or seafood fraud, whereby one species of seafood is substituted with a less desirable, cheaper, or more readily available species. Typically similar in taste and texture, certain marine species are difficult to identify without diagnostic body parts such as its head, skin, fin, or shells. Once filleted and prepared, it is often difficult to decipher the exact species that is being served.

Species which are commonly mislabeled include Atlantic cod, grouper, swordfish, red snapper, and wild salmon. When processed, these species become extremely difficult to identify

Seafood fraud is detrimental for multiple reasons. First, it can threaten human health as certain fish species contain high concentrations of contaminants and toxins (1). King Mackerel generally contains high concentrations of mercury, and Escolar (typically sold as white tuna) produces a toxin that leads to gastrointestinal issues. Unknowingly consuming these species can pose serious health risks. Second, global fish stocks face increasing pressure daily from exploitation and overfishing. Mislabeling can create and sustain markets for illegal fishing (2). As laundering illegal species becomes easier, conservation efforts become weakened. Shockingly, according to the US Government Accountability Office, only 2% of seafood imported into the US is inspected and of that, only 0.001% is inspected for fraud (3).

Mislabeling can also undermine consumer’s choices by making it difficult for them to accurately make a sustainable seafood purchase. And finally, it misleads the public about the truth surrounding the availability and conservation status of certain species (3). Instead, it gives an exploited fish species, such as Grouper, the false appearance of having a steady supply.

Fortunately, a number of studies are helping to educate and bring awareness to the severity of seafood fraud and more importantly potential solutions to counter the prevalence of this issue. Hanner et al., in 2011, found 41% of their 254 Canadian seafood samples to be mislabeled. Pacific salmon was often not designated to a species level (e.g. Coho, Sockeye, Pink), Red Snapper was commonly swapped with Tilapia, and there were instances of Patagonian Toothfish being labeled as Chilean Seabass; all of these examples of mislabeling (4).

To help study and combat this practice, researchers, including Hanner, have been using DNA barcoding, where they match genetic material of a fish sample against known genetic sequences, or barcodes, in a database. The benefit of using DNA barcoding is its ability to match barcodes from whole fish, fillets, fins, juveniles, eggs, and even samples of cooked or frozen fish! As our voracious appetite for seafood consumption outpaces the supply, global fish stocks continue to decline. DNA barcoding offers an effective way to increase transparency, fair trade, and ultimately ensure a more sustainable future for the global seafood industry and for stronger fisheries resource management.

Organizations like Oceana have also produced studies shedding light on seafood fraud. From 2010 to 2012, they analyzed over 1200 seafood samples across the United States, and found a mislabeling rate of 33% across 21 states (1). Popular metropolitan cities such as Miami, Washington DC, Seattle, New York City, and even land-locked cities like Austin, Denver, and Kansas City were culprits. With numbers from these studies, a conservative worldwide mislabeling rate of just 10% would indicate that there is around $24 billion in fraudulent seafood shipped worldwide annually (4)! Studies have also uncovered widespread mislabeling in Brazil, South Africa, the Philippines, Italy, and the UK, which supports the reality that seafood substitution is not confined by geographic boundaries or species.

Coupled with these studies that raise awareness about mislabeling, increased education of consumers can be another effective tool for the conservation of commercially harvested species that could be threatened or endangered. Miller et al. in 2011, examining mislabeling in the UK and Ireland, found Cod mislabeling to be about 4 times lower in the UK than Ireland. This was credited mainly to heightened consumer awareness in the UK despite the same EU policies for seafood traceability and labeling across both countries (5). Consumer education coupled with accurate labeling would allow consumers to make more informed choices and control the demand for more sustainable seafood.

As more light is being shed on this issue, programs are being developed to help combat seafood mislabeling. From edible QR codes which diners can scan to download harvesting information about their fish, to ‘trip tickets’ allowing consumers to track their seafood from harvest to plate, these initiatives are helping raise consumer awareness. Through these programs and others, consumers can gain the power to influence stricter labeling standards for the future to help enhance traceability in the global seafood trade and to help further support truly sustainable fisheries.

References

- “Seafood Fraud: Overview.” 2012. Oceana. Retrieved November 17, 2013, from http://oceana.org/en/our-work/promoteresponsible-fishing/seafoodfraud/overview

- Carvalho, D. C., Neto, D. A., Brasil, B. S., & Oliveira, D. A. (2011). DNA barcoding unveils a high rate of mislabeling in a commercial freshwater catfish from Brazil. Mitochondrial DNA, 22(S1), 97-105.

- GAO, U. (2009). Seafood Fraud: FDA Program Changes and Better Collaboration Among Key Federal Agencies Could Improve Detection and Prevention.

- Hanner, R., Becker, S., Ivanova, N. V., & Steinke, D. (2011). FISH-BOL and seafood identification: Geographically dispersed case studies reveal systemic market substitution across Canada. Mitochondrial DNA, 22(S1), 106-122.

- Miller, D., Jessel, A., & Mariani, S. (2012). Seafood mislabeling: comparisons of two western European case studies assist in defining influencing factors, mechanisms and motives. Fish and fisheries, 13(3), 345-358.