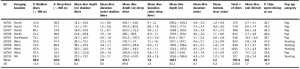

By Daniela Escontrela, RJD Intern

The Galapagos Islands are home to four species of native and endemic boobies: the blue footed boobies, the masked boobies, the Nazca boobies and the red footed boobies. The name for the boobies comes from the name “bobo” which is a Spanish term for fool or clown. They are all part of the Gannet family which is also found in North America. These birds have dagger like beaks and are accustomed to diving into the ocean for their food. Although the three species of boobies nest and breed in approximately the same territories they don’t fish near each other. The blue footed boobies feed close to shore, the masked boobies farther out and the red footed boobies even farther out. The masked booby is the biggest of all the boobies; they are mostly white colored with black tail feathers and black primary feathers at the end of their wings. They have a yellow beak, with the females sporting a paler beak than the males. The term “masked” booby comes from the black skin at the base of their beak that makes it look like they are wearing a mask. Although the masked booby feeds itself by plunge diving, like the other boobies, this is rarely observed as it feeds farther offshore. These birds breed on an annual cycle, but each island has their own times for breeding. Like the other boobies, they have courtship rituals and dances but they are far less intricate than those of the blue footed boobies. The masked booby will lay two eggs but only one of them will hatch and be reared by the parents. These birds can often be found laying eggs on the islands of Espanola, San Cristobal and Genovesa. (Fitter et al 2000).

An image of a Nazca booby at Roca Union near the island of Isabela, Galapagos. Photo by Daniela Escontrela

The Nazca booby, which is native to the Galapagos, is a separate species than the masked booby but they are closely related and share a lot of the same characteristics and behaviors. Nazca boobies when young experience two types of maltreatment or violence: obligate siblicide and interactions with non-parental adult visitors. The cycle of violence hypothesis which has been tested on human subjects states that child abuse may be a cause violent behavior later in life. Nazca boobies provide a non-human model to test these hypothesis as the chicks are often subject to abuse, either from siblings or from nonfamilial adults. (Muller et al, 2011) Using the cycle of violence hypothesis, we predict that Nazca booby chicks subjected to these types of interactions may be more predisposed as adults to engage in similar aggressive activities, such as becoming non-parental adult visitors themselves. Furthermore, we predict that the predisposition of violent episodes experienced by adult Nazca boobies may be correlated with increased amounts of hormone release.

Nazca boobies vary in the size of the clutch they lay and it has been found that clutch size can often be related to the female’s food limitation (Humphries et al, 2005). The only reason the original clutch size may exceed more than one egg is because the second egg provides an insurance in case the first egg fails to hatch (Ferree et al, 2004). However, even though boobies often lay two or more eggs, usually only one of the chicks makes it to independence. The reason for this is that Nazca boobies practice a behavior termed obligate siblicide where aggression from a core chick often causes the mortality of the marginal chick which results in a brood reduction. (Humphries et al, 2005). Siblicide is often described as a form of a lethal attack coming from a sibling; if both eggs hatch, one chick will kill the other usually by pushing it off the nest. Once pushed off, the chick usually dies due to starvation, exposure or predation. Rarely does the chick make it back to the nest. (Ferree et al, 2004) In a study, very rarely did two chicks from one clutch make it to independence because of obligate siblicide. In the few cases two chicks made it to independence, one of the chicks was usually in such poor condition it almost didn’t make it. (Humphries et al, 2005)

Another form of aggression or maltreatment Nazca booby chicks experience is interactions with non-parental adult visitors (NAVs). In this interaction, adults tend to show an attraction to offspring of other parents which is often sexually or aggressively motivated. (Muller et al, 2011). There seems to be no reward for the adults that engage in this behavior while the chicks can often be injured (Grace et al, 2011). In Nazca booby communities this aggression or attraction to other nonfamilial young is common and most adult boobies engage in these acts at least once in their life. Nazca boobies are often raised as solitary nestlings (because the other chick is usually killed by obligate siblicide) in dense colonies were there are large probabilities for these NAV interactions. (Muller et al, 2011) In fact most nestlings experience NAV interactions at least once during their nesting period (Grace et al, 2011). NAV events usually occur when chicks are between 30 and 80 days old and usually happen because the chicks are left unattended while the parents go out and forage for food. When unattended by the parent, nonbreeding adults will seek the chicks for social interactions. These NAV events are less common when parents are around because the parents will chase away these adults. (Muller et al 2011)

A non-parental adult visitor (NAV) exhibits aggressive behavior (Grace et al, 2011)

There has been a positive correlation between the number of attacks chicks received (either from siblings or other adults) and the number of times the same chick participated in NAV behavior as an adult. The attacks received by the chicks at early stages of life affect and mold individual personalities. Although the siblicide behavior is a strong predictor of adult behavior, NAV events tended to contribute more to molding individual adult behavior. This shows that experiences as chicks can mold adult social behavior (Muller et al 2011).

Testosterone is a hormone released to mediate aggression. Testosterone is usually released when the argenine vasotocin system is stimulated. However, release of this hormone can be energetically expensive, especially if it has to be up-regulated for long periods of time. For this reason, according to the challenge hypothesis, testosterone is up-regulated only during social challenges. These social challenges include sibling aggression and interactions with NAVs which can be seen as times of fighting. After a study was conducted, it was found that testosterone levels tended to increase in the chicks during times of attack by NAVs or siblings. The chick being attacked tended to have higher testosterone levels than the attacker. In the case of obligate siblicide, the marginal chicks were often found to have higher levels of testosterone, even during times of no attack, because the core chicks represented such a threat. (Ferree et al, 2004) Another hormone, corticosterone which is associated with stress responses, was increased five-fold during maltreatment episodes (Grace et al, 2011).

Maltreatment behavior as adults is still not really understood. So far, three hypothesis have been proposed for the increased frequency of attacks inquired by adult Nazca boobies. One of the hypothesis predicts that “maltreatment in early life causes long term neuroendocrine changes that underline later maltreatment tendencies”. During NAV events, the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis response is induced in the nestling under attack. Repeated activation of the HPA axis may lead to long term endocrine changes which could carry on to adulthood. These acute changes in the HPA axis experienced by chicks induced during NAV episodes, if repeated often, may increase the chances that the individual will engage in more NAV behavior as an adult. In fact, adults engaging in NAV events have been found to have higher levels of circulating corticosterone and lower testosterone levels than those adults that are non-engaged in this behavior. These difference in hormone levels may be a result of repeated maltreatment events in early life which resulted in permanent neuroendocrine modifications. The other two hypothesis that may explain increased frequency of NAV behavior as adults is that the behavior is acquired through observational learning or that it is a genetically heritable trait. However, not much evidence or research has been done to prove these hypotheses so they must be ruled out until more research is performed. (Grace et al, 2011)

Nazca booby chicks experience obligate siblicide and NAV events in the early stages of their development. These events have been found to mold individual adult behavior; as a chick is exposed to more of either of the two events, the more likely the chick is to be involved in NAV interactions as an adult. As chicks are subjected to these maltreatment events, the HPA axis is also induced, causing changes in hormone levels. This repeated activation of the HPA axis as a chick may cause long term endocrine changes that can carry on to adulthood. These endocrine changes may be the underlying factor that cause these individuals to be more predisposed to engage in NAV events as adults.

References

Ferree, E. D., Wikelski, M. C., & Anderson, D. J. (2004). Hormonal Correlates of Siblicide in Nazca Boobies. Hormones and Behavior, 46, 655-662.

Fitter, J., Fitter, D., & Hosking, D. (200). Wildlife of the Galapagos. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press.

Grace, J. K., Dean, K., Ottinger, M. A., & Anderson, D. J. (2011). Hormonal effects of maltreatment in Nazca booby nestlings: implications for the “cycle of violence”. Hormones and Behavior, 60, 78-85.

Humphries, C. A., Arevalo, D., Fischer, K. N., & Anderson, D. J. (2005). Contributions of marginal offpsring to reproductive success of Nazca booby (Sula granti) parents: tests of multiple hypothesis. Behavioral Ecology, 147, 379-390.

Muller, M. S., Porter, E. T., Grace, J. K., Awkerman, J. A., Birchler, K., Gunderson, A. R., . . . Anderson, D. (2011). Maltreated nestlings exhibit correlated maltreatment as adults: evidence of a “cycle of violence” in Nazca boobies (Sula granti). The Auk, 1-19.