Clean, Clear, and Under Environmental Control: The Coal Mining Industry’s Impact on the Great Barrier Reef

By Casey Dresbach, SRC Intern

Australia’s Great Barrier Reef is home to 348,000 km (approximately 216237.175 miles) of marine ecosystems, an expansive realm is almost equivalent to the size of Germany. However, its grand location is at mercy to shipping channels, rail transport networks, major ports, and most detrimental, several coal mines. In July 2015, the World Heritage Committee called attention to the consequences of these coal deposits. Climate change, poor water quality, and coastal development are jeopardized for industrial preference. This multi-billion dollar coal industry is great economically but scientifically, the cons outweigh the pros. They are not particularly fixing anything. They seem to touch upon the short-term effects and not the long term. Research has shown that the integration of both short and long term impacts could potentially serve a far more effective plan for change.

Photograph of The Great Barrier Reef shot from a helicopter ride over the Reef at the Whitsunday Islands, Australia.).

Coal power plant emissions contain several toxic elements that suffocate the environment. Global warming comes hand in hand with the emissions as far too much C02 is released into the air. Not only do those emissions affect the air but also the ocean’s pH level. Ocean acidification becomes the reality, which ultimately leads to bleaching of the corals. Environmental impact statements (EISs) are currently instated to assist Australian Governments and Queensland to consider the impact of new coal mining proposals when deciding whether to approve them and inform the development of appropriate conditions for environmental management. Their role is to describe the environment’s current state which is extremely beneficial but the problem here is that they only report direct local impacts of mining operations and do not consider the indirect impacts of the mines at a broader spatial or temporal scale. Australia’s Reef is massive and the EISs do not consider its vastness. It is so crucial to understand the incremental accumulation of impacts, which have led to its own decline.

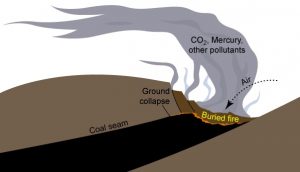

Schematic condition of a mine fire configuration, with emissions of dust, fine particles, radon, mercury vapor, CO, CO2, NOx, SO2, etc… source pollution and gas contributing to the greenhouse effect.).

A World Heritage Site is a place that is listed by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) as being of special physical significance. The Great Barrier Reef is categorized as such and the failure of the EISs to consider the progressive factors coal mining inundates has led to sharp decreases in World Heritage values.

An alternative assessment to the EISs is the Cumulative Impact Assessment (CIA) which systematically analyzes, evaluates, and predicts cumulative environmental change over time and across a grand spatial extent of a particular environment, focusing on pressures of interactions. For example, they would hone into the negatives of coal mining in combination with already polluted land from said mining. They might also combine such interaction with the present coastal development and its potential impact on climate change. CIAs are all encompassing and they focus on the broader, the potential, what could happen in time to come.

We should make the CIA the primary choice of assessment even though there are barriers to cumulative impact assessments. The Reef 2050 Plan is the framework set for protecting and managing the Great Barrier Reef from 2015 to 2050. The issue is that it hasn’t managed to establish accuracy in long-term research models. They focus on qualitative studies rather than the broader interactive research to better understand potential problems in the future. The continuing of such failure will send us back to EISs, which are far from influential leading to more piecemeal decisions that ignore the lengthy and extensive accumulation of impacts responsible for the Reef’s decline.

Moving forward, independent CIA commissions should be instated to se the terms of reference, review the assessment’s outputs by deeming them continuous or not, and initiating public input by ensuring well established time frames and focusing on the long term issues. The Great Barrier Reef should most definitely have precedence over the coal industry because coal isn’t the hottest commodity today. Given its predicted to slow anyway, Australia Bank is no longer planning to fund mining projects. Neither are Deutsche Bank, HSBC, Morgan Stanley, Citigroup and other lenders because they’re nervous of jeopardizing their reputations. The consequences the coal industry allocates to the environment are no secret yet the trade still seems to continue its operation year after year. All potential funders are aware of the negatives and don’t want their names paired with such negativity. We need to standardize and focus on the long term issues of coal mining and less so on the business or monetary gains from the industry.

References

Ackerman, S. (2009, December 27). Amazing Great Barrier Reef 1. Retrieved January 11, 2015, from Wikimedia Commons: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Amazing_Great_Barrier_Reef_1.jpg

Bretwood Higman, G. T. (n.d.). Coal Seam Fire. Retrieved from Ground Truth Trekking: http://www.groundtruthtrekking.org/Graphics/CoalSeamFires.html

Grech, A., R. L. Pressey, and J. C. Day. “Coal, Cumulative Impacts, and the Great Barrier Reef.” Conservation Letters (2015).