Shark Nurseries

Some shark species rely on specific locations or habitats during early life. These areas—known as shark nurseries—provide young sharks with conditions they need to grow and survive, which can include better access to food, suitable environmental conditions, or reduced exposure to predators. Because survival during early life strongly influences population stability, identifying and protecting nursery habitats is a key component of shark conservation.

Scientists determine an area is a shark nursery by looking at three key factors (from Heupel et al. 2007): whether juvenile sharks are more common within the potential nursery area than outside it, whether they spend significant time periods within the nursery, and whether the nursery remains in use across multiple years.

Our research has shown that Biscayne Bay functions as an important nursery habitat for multiple shark species. Juvenile sharks of multiple species are encountered throughout the Bay, with some exhibiting strong residency and site fidelity, and many species documented there year after year. Long-term monitoring, tag-recapture data, acoustic telemetry, and stable isotope analysis all suggest that many young sharks use Biscayne Bay not just as a temporary refuge, but as core habitat. These patterns mean many species meet all three nursery criteria, highlighting the bay’s importance for sustaining regional shark populations.

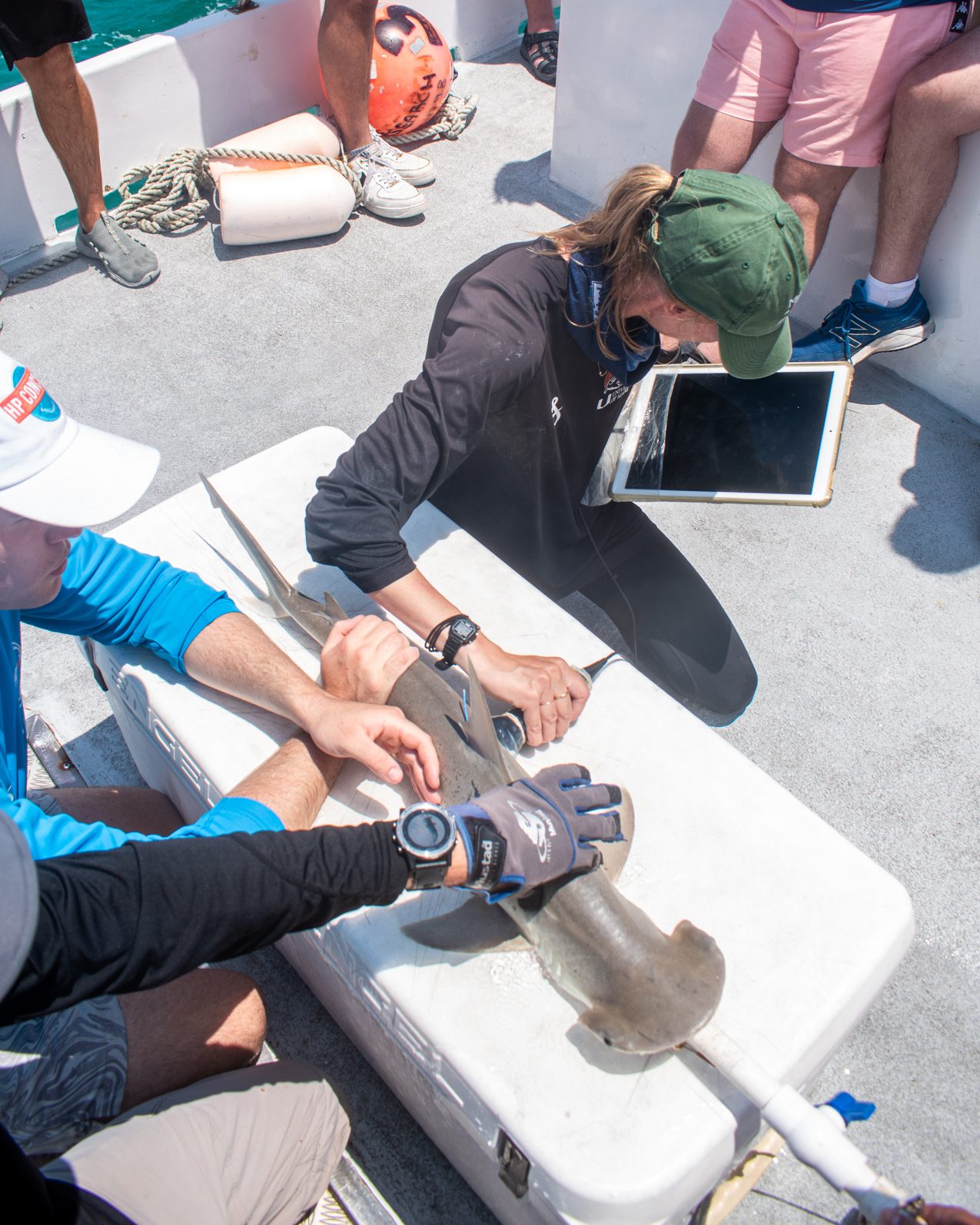

The SRC team studies shark nurseries using a combination of long-term field monitoring, biological sample collection, telemetry, and non-invasive (e.g., drone) surveys. We assess residency, habitat use, growth, and environmental conditions to understand how nursery habitats support early life stages—and how human-driven changes may alter their function.

Shark Reproductive Biology

A critical part of our research focuses on shark reproductive biology—when and where animals mate, how long pregnancies last, and how reproductive cycles vary across species and environments. These life-history processes shape population growth and recovery, yet remain poorly documented for many shark and ray species.

Our team works to identify pregnant individuals and characterize reproductive stages by combining multiple scientific tools. We use hormone analysis from blood samples to assess reproductive condition and track changes in hormones associated with mating, and to study ovulation, pregnancy, and parturition (birth). These data are paired with ultrasound imaging, which allows us to directly visualize developing embryos and estimate pup development.

We can also document mating periods and reproductive behaviors through field observations, tagging data, and acoustic telemetry targeting fine-scale movement patterns. By integrating physiology, behavior, and environmental context, we can identify which habitats are most important during reproduction. This can improve our ability to protect breeding adults, pupping areas, and nursery habitats. This work provides essential information for conservation planning and management of shark populations under increasing environmental and human pressure.

Check out this Instagram Reel to follow along as SRC PhD Student Candy sorts through hundreds of plasma samples and extracts hormones in preparation for analysis. Candy’s research is helping build reproductive hormone profiles for male and female blacktip sharks (C. limbatus)—critical information for managing and protecting shark populations and the ecosystems they rely on for reproduction!

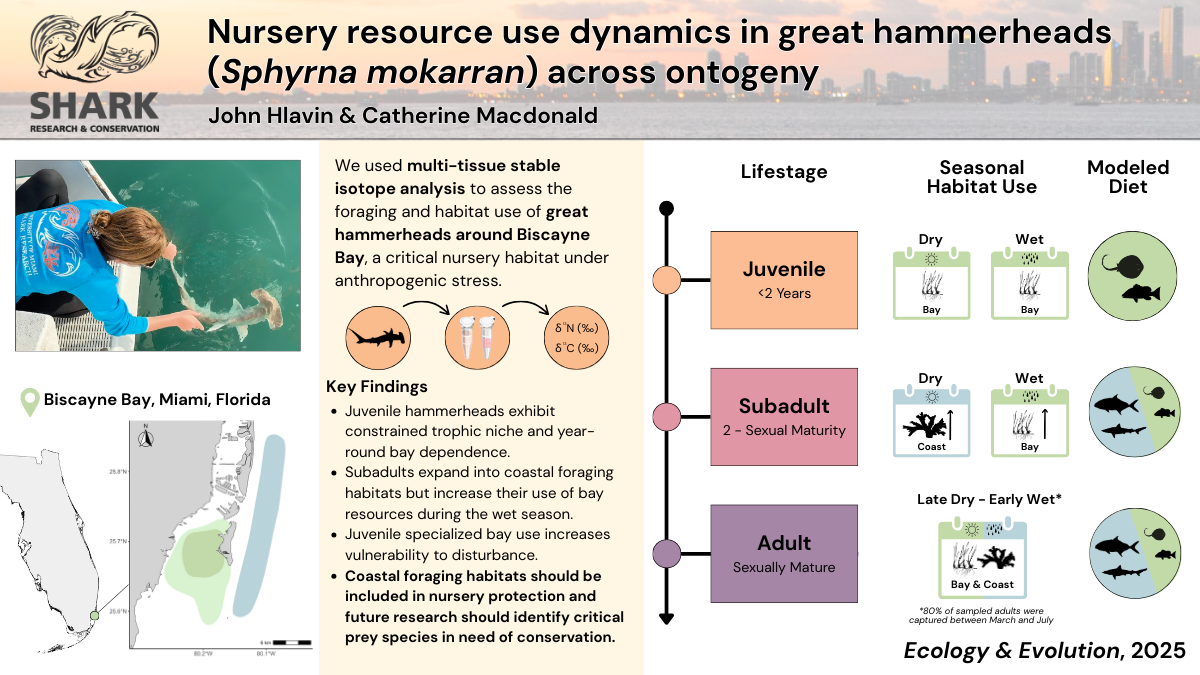

Hlavin, J., Macdonald, C. (2025). Nursery resource use dynamics in great hammerheads (Sphyrna mokarran) across ontogeny. Ecology and Evolution 15(6), e71473. https://doi.org/10.1002/ece3.71473

Giesy, K., Jerome, J., Wester, J., D’Alessandro E., McDonald, D., Macdonald, C. (2025). The physiological stress response of juvenile nurse sharks (Ginglymostoma cirratum) to catch-and-release recreational angling. PLoS One, 20(1), e0316838. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0316838

Black, K.., Liu, K. , Graham, J., Wiley, T., Gardiner, J., Macdonald, C., Matz, M. V. (2024). Evidence of unidirectional gene flow in Bonnethead sharks from the Gulf to Atlantic coasts of Florida. Ecology and Evolution 14(9), e70334. https://doi.org/10.1002/ece3.70334

Macdonald, C., Jerome, J., Pankow, C., Perni, N., Black, K. †, Shiffman, D., & Wester, J. (2021). First identification of probable nursery habitat for critically endangered great hammerhead Sphyrna mokarran on the Atlantic Coast of the United States. Conservation Science and Practice, 3(8), e418. https://doi.org/10.1111/csp2.418

Pankow, C.J., Macdonald, C., Shiffman, D.S., Wester, J., & Abel, D. (2021). Stable isotopic dynamics of juvenile elasmobranchs in a South Carolina nursery area. Southeastern Naturalist, 20(1), 92–104. https://doi.org/10.1656/058.020.0107

In Focus: Evidence for Biscayne Bay as a Shark Nursery

A key study supporting Biscayne Bay’s role as a shark nursery was recently published by Shark Research & Conservation (SRC) PhD student John Hlavin and our director. The study used stable isotope analysis to examine feeding ecology and resource use of juvenile great hammerhead sharks. Stable isotopes act as natural tracers, allowing researchers to infer where sharks are feeding and how long they remain associated with specific habitats.

Our results showed that juvenile great hammerheads exhibited isotopic signatures consistent with prolonged residency and local feeding within Biscayne Bay, rather than brief or transient use of the area. This provided independent, chemical evidence that young hammerheads rely on the bay during early years of life. Importantly, this approach complements tagging and survey data by capturing habitat use over longer time scales, even when sharks are not actively being tracked.

Together, these findings strengthen the case for Biscayne Bay as a great hammerhead nursery habitat and highlight the value of combining multiple, independent types of evidence to identify and validate shark nurseries, particularly in highly urbanized coastal ecosystems.