Overview

Climate change is having, and will continue to have, enormously varied effects on global oceans. Overall, we can expect changes including:

Climate change has serious implications for ecosystems and wildlife, but the effects of warming are especially hard to study in highly mobile marine animals, such as large sharks. Most sharks’ body temperature and metabolism is shaped by the temperature of the surrounding environment, as they are ectotherms and do not warm their bodies through metabolic heat production (with a few exceptions). Like other animals, sharks have an ideal range for temperature, above or below which they are negatively affected. Scientists can measure animal responses to different temperatures in controlled lab settings very precisely. For larger marine animals, including many coastal shark species, studying climate change in the lab is not feasible, and so these kinds of research can present logistical challenges. At SRC, we are conducting a series of research projects to begin exploring the effects of climate variability on sharks. Related projects include:

Study Highlight

Ocean warming alters the distributional range, migratory timing, and spatial protections of an apex predator, the tiger shark (Galeocerdo cuvier).

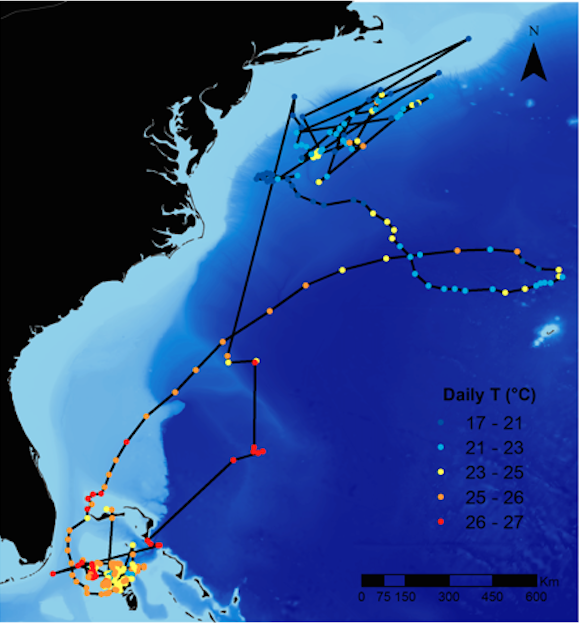

In a collaborative study, the SRC team used multiple approaches to evaluate the effects of ocean warming on tiger shark movements in the Western North Atlantic. This research found that over the past ~40 years, shark distributions have expanded northward, paralleling rising temperatures. Moreover, satellite tracking of sharks over the past decade has revealed their annual migrations have extended farther poleward and arrival times to northern areas have also occurred earlier in the year during warm periods, which has subsequently decreased their spatial overlap with time/area closures which may protect them from fisheries interactions. Potential consequences of these climate-driven alterations include increasing shark vulnerability to fishing, disruption of predator-prey interactions and changes in encounter rates with human water-users.

Figure: A year-long migration of a female tiger shark beginning in the Bahamas, travelling as far north as the state of Massachusetts. Point colors show water temperature sensed by the shark-borne satellite tag.(Figure via Rachel Skubel)

SRC In Focus

Scientific Publication:

Hammerschlag N, McDonnell LH, Rider MJ, Street GM, Hazen EL, Natanson LJ, McCandless CT, Boudreau MR, Gallagher A J, Pinsky ML, Kirtman B (2022). Ocean warming alters the distributional range, migratory timing, and spatial protections of an apex predator, the tiger shark (Galeocerdo cuvier). Global Change Biology, 00, 1–16.https://doi.org/10.1111/gcb.16045

Gutowsky LF, Rider M, Roemer RP, Gallagher AJ, Heithaus MR, Cooke SJ, Hammerschlag N. (2021) Large sharks exhibit varying behavioral responses to major hurricanes. Estuarine, Coastal and Shelf Science. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecss.2021.107373

Skubel RA, Kirtman BP, Fallows C, Hammerschlag N (2018) Patterns of long-term climate variability and predation rates by a marine apex predator, the white shark Carcharodon carcharias. Marine Ecology Progress Series 587:129-139.