Tracking Sharks

Overview

The Shark Research and Conservation (SRC) Program uses satellite and acoustic telemetry together to understand how sharks use habitats like Biscayne Bay during critical life stages, including for reproduction and early life. These tagging methods provide different but complementary information about shark habitat use, and integrating both allows us to study movement across multiple spatial and temporal scales.

Satellite tags are used to track broad-scale movements of juvenile sharks and pregnant females across coastal and offshore environments. These tags provide near-real-time location data, allowing us to follow shark movements as they occur and identify long-distance migrations, dispersal pathways, and connectivity between offshore habitats and coastal nursery areas. In addition to location information, satellite tags can also record environmental data such as water temperature and depth, giving insight into physical conditions in different shark habitats.

Acoustic tags provide fine-scale, long-term data on habitat use within specific areas. When sharks pass near acoustic receivers, their presence is recorded, allowing us to quantify residency, site fidelity, and seasonal habitat use within known or suspected nursery habitats. Acoustic telemetry is especially effective for determining how long juveniles remain in nursery areas, whether individuals return to the same habitats over time, and how habitat use changes across seasons and as individuals grow.

By integrating satellite and acoustic telemetry with other forms of data, our work addresses questions across multiple shark species, including Hammerhead, Blacktip, and Tiger Sharks:

1 – Where are habitats important for reproduction, including nurseries and gestation areas, located for different species in South Florida?

2- How do movements of pregnant females connect offshore habitats with coastal nursery areas, and do females show consistent use of particular regions prior to giving birth?

3 – How do juvenile sharks spend their time within nursery habitats, including patterns of residency, site fidelity, and seasonal habitat use?

4 – When and how do juveniles begin to expand their range beyond nurseries, and how may this transition differ across species?

5 – To what extent do reproductive habitats and juvenile movement pathways overlap with disturbed or urbanized habitats, and how does habitat quality affect habitat use?

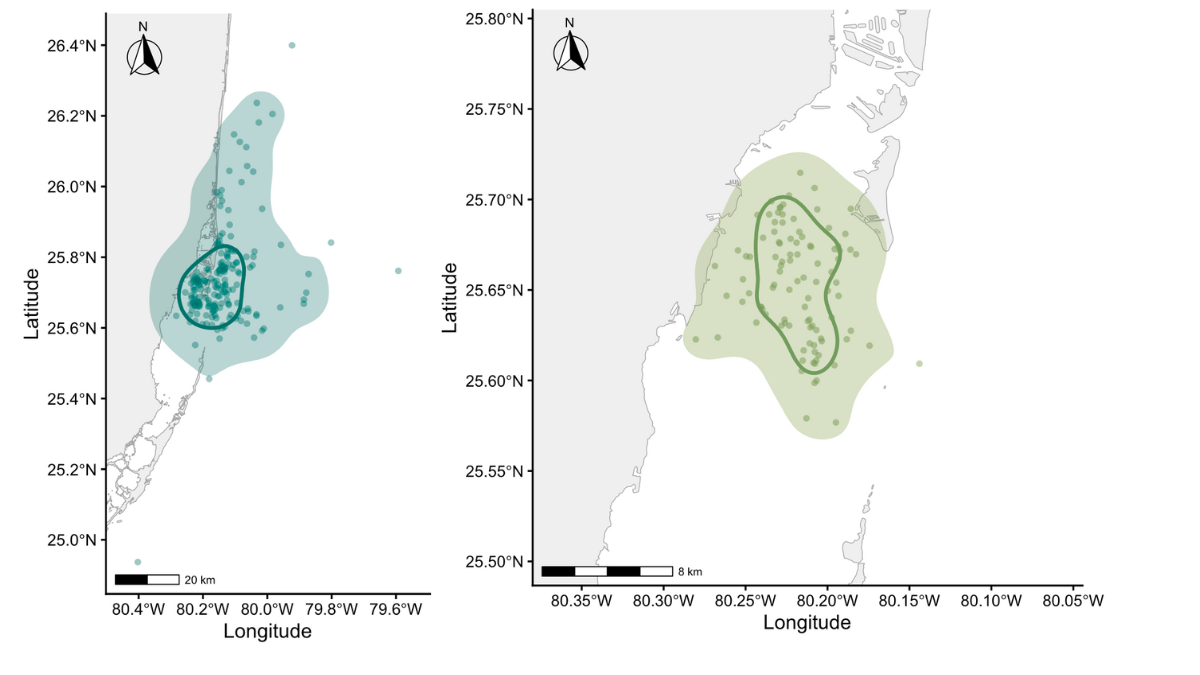

Example output from satellite telemetry in Biscayne Bay.

Satellite tags deployed on juvenile sharks in Biscayne Bay allow us to map movements across coastal habitats, showing where individuals spend time and how they use space over weeks to months. Points represent satellite location estimates, while the shaded areas depict overall home-range use and core activity areas from these data. This type of information helps identify important habitats and patterns of space use.

Previous SRC Studies

In a study published in the journal Nature, an international team of scientists, including SRC researchers, combined movement data from nearly 2,000 sharks tracked with satellite tags. Using this tracking information, the collaborative research team identified areas of the ocean that were important for multiple species, shark “hot spots”, that were generally located in ocean frontal zones, which are boundaries in the sea between different water masses that are highly productive and food-rich. We then calculated how much shark hot spots overlapped with global longline fishing effort– the type of fishing gear that catches most open-ocean sharks. Our study found that 24% of the space used by sharks in an average month also experiences longline fishing. For commercially exploited shark species such as blue and shortfin makos sharks in the North Atlantic, the overlap was much higher, with on average 76% and 62% of their space use, respectively, overlapping with longlines each month. Currently, little protection exists for sharks in the high seas. It’s clear from this study that conservation action is needed to prevent further declines of open-ocean sharks. The study proposed that designated large-scale marine protected areas around regions of shark activity could be one solution. Our study provides detailed maps of shark hot spots overlapping with longline fishing, essentially providing a ‘blueprint’ for deciding where to place large-scale marine protected areas (MPAs) aimed at conserving sharks, in addition to the need for shark quotas to reduce catches elsewhere.

The video below is a visual overview of a paper we published in the Journal of Functional Ecology based on our satellite tagging research.

Publications

Calich HJ, Rodríguez JP, Eguíluz VM, Hammerschlag N, Pattiaratchi C, Duarte CM, Sequeira AM. (2021) Comprehensive analytical approaches reveal species-specific search strategies in sympatric apex predatory sharks. Ecography https://doi.org/10.1111/ecog.05953

Sequeira AM, O’Toole M, Keates TR, McDonnell LH, Braun CD, Hoenner X, Jaine FR, Jonsen ID, Newman P, Pye J, Bograd SJ, et al. (2021) A standardisation framework for bio‐logging data to advance ecological research and conservation. Methods in Ecology and Evolution. https://doi.org/10.1111/2041-210X.13593

Friess C, Lowerre-Barbieri SK, Poulakis GR, Hammerschlag N, et al. (2021) Regional-scale variability in the movement ecology of marine fishes revealed by an integrative acoustic tracking network. Friess et al. 2021_egional-scale variability in the movement ecology of marine fishes. Marine Ecology Progress Series 663:157-177. https://doi.org/10.3354/meps13637

Rider MJ, McDonnell LH, Hammerschlag N. (2021) Multi-year movements of adult and subadult bull sharks (Carcharhinus leucas): philopatry, connectivity, and environmental influences. Aquatic Ecology https://doi.org/10.1007/s10452-021-09845-6

Gallagher AJ, Shipley ON, van Zinnicq Bergmann MPM, Brownscombe JW, Dahlgren CP, Frisk MG, Griffin LP, Hammerschlag N, Kattan S, Papastamatiou YP, Shea BD, Kessel ST, Duarte CM (2021) Spatial Connectivity and Drivers of Shark Habitat Use Within a Large Marine Protected Area in the Caribbean, The Bahamas Shark Sanctuary. Frontiers in Marine Science 7:608848. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2020.608848

Morgan A, Calich C, Sulikowski J, Hammerschlag N. (2020) Evaluating spatial management options for tiger shark (Galeocerdo cuvier) conservation in US Atlantic Waters. ICES Journal of Marine Science, fsaa193, https://doi.org/10.1093/icesjms/fsaa193

Skubel RA, Wilson K, Papastamatiou YP, Verkamp HJ, Sulikowski JA, Benetti D, Hammerschlag N. (2020) A scalable, satellite-transmitted data product for monitoring high-activity events in mobile aquatic animals. Anim Biotelemetry 8, 34. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40317-020-00220-0

Ajemian MJ, Drymon JM, Hammerschlag N, Wells RJD, Street G, Falterman B, et al. (2020). Movement patterns and habitat use of tiger sharks (Galeocerdo cuvier) across ontogeny in the Gulf of Mexico. PLoS ONE 15(7): e0234868. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0234868

Queiroz N, et al. (2019). Global spatial risk assessment of sharks under the footprint of fisheries. Nature, doi: 10.1038/s41586-019-1444-4

Hays GC, Bailey H, Bograd SJ, Bowen WD, Campagna C, Carmichael RH, Casale P, Chiaradia A, Costa DP, Cuevas E, Bruyn PJND, Dias MP, Duarte CM, Dunn DC, Dutton PH, Esteban N, Friedlaender A, Goetz KT, Godley BJ, Halpin PN, Hamann M, Hammerschlag N, et al. (2019). Translating Marine Animal Tracking Data into Conservation Policy and Management; Trends in Ecology & Evolution; 34(5): 459-473.

Rooker JR, Dance MA, Wells RJD, Ajemian MJ, Block BA, Castelton MR, Drymon JM, Falterman BJ, Franks JS, Hammerschlag N, Hoffmaer ER, Kraus RT, McKinney JA, Secor DH, Stunz GW, Walter JF. (2019) Population connectivity of pelagic megafauna in the Cuba-Mexico-U.S. triangle. Scientific Reports; 9 (1663) https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-38144-8

Calich H, Estevanez M, Hammerschlag N. (2018). Overlap between highly suitable habitats and longline gear management areas reveals vulnerable and protected regions for highly migratory sharks. Marine Ecology Progress Series 602: 183-195

Sequeira AMM, Rodríguez JPP, Eguíluz VM, Harcourt R, Hindell M, Sims DW, Duarte CW, Costa DP, Fernández-Gracia J, Ferreira LC, Hays GC, Heupel MR, Meekan MG, Aven A, Bailleul F, Baylis AMM, Berumen ML, Braun CD, Burns J, Caley MJ, Campbell R, Carmichael RH, Clua E, Einoder LD, Friedlaender A, Goebel ME, Goldsworthy SD, Guinet C, Gunn J, Hamer D, Hammerschlag N, Hammill M, Hückstädt LA, Humphries NE, Lea MA, Lowther A, Mackay A, McHuron E, McKenzie J, McLeay L, McMahon CR, Mengersen K, Muelbert MMC, Pagano AM, Page B, Queiroz N, Robinson PW, Shaffer SA, Shivji M, Skomal GB, Thorrold SR, Villegas-Amtmann S, Weise M, Wells R, Wetherbee B, Wiebkin A, Wienecke B, Thums M. (2018). Convergent movement patterns of marine megafauna. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. DOI: 10.1073/pnas.1716137115

Acuña-Marrero D, Smith ANH, Hammerschlag N, Hearn A, Anderson MJ, Calich H, et al. (2017). Residency and movement patterns of an apex predatory shark (Galeocerdo cuvier) at the Galapagos Marine Reserve. PLoS ONE 12(8): e0183669. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0183669

Klimley AP, Flagg M, Hammerschlag N, Hearn A. (2017). The value of using measurements of geomagnetic field in addition to irradiance and sea surface temperature to estimate geolocations of tagged aquatic animals. Animal Biotelemetry; 2;5(1): 19.

Graham F, Rynne P, Estevanez M, Luo J, Ault JS, Hammerschlag N. (2016). Use of marine protected areas and exclusive economic zones in the subtropical western North Atlantic Ocean by large highly mobile sharks. Diversity and Distributions; 22(5): 534-546.

Queiroz N, Humphries N.E., Mucientes G., Hammerschlag N, Lima F.P, Scales K.L, Miller P.I., Sousa L.L., Seabra R., Sims D.W. (2016). Ocean-wide tracking of pelagic sharks reveals extent of overlap with longline fishing hotspots. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences; 113(6): 1582-1587.

Hammerschlag N, Broderick AC, Coker JW, Coyne MS, Dodd M, Frick MG, Godfrey MH, Godley BJ, Griffin DB, Hartog K, Murphy SR, Murphy TM, Nelson ER, Williams KL, Witt MJ, Hawkes LA (2015). Evaluating the landscape of fear between apex predatory sharks and mobile sea turtles across a large dynamic seascape. Ecology, 96(8): 2117-2126.

Hammerschlag N, Cooke SJ, Gallagher AJ, Godley BJ. (2013). Considering the fate of electronic tags: user responsibility and interactions when encountering tagged marine animals; Methods in Ecology and Evolution; 11(5): 1147-1153.

Hammerschlag N, Luo J, Irschick DJ, Ault JS (2012) A Comparison of Spatial and Movement Patterns between Sympatric Predators: Bull Sharks (Carcharhinus leucas) and Atlantic Tarpon (Megalops atlanticus). PLoS ONE 7(9): e45958. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0045958

Hammerschlag N, Gallagher AJ, Wester J, Luo J, Ault JS. 2012 (Cover). Don’t bite the hand that feeds: assessing ecological impacts of provisioning ecotourism on an apex marine predator. Functional Ecology, 26(3): 567-576

Hammerschlag N, Gallagher AJ, Lazarre DM. (2011) A Review of Shark Satellite Tagging Studies. Journal of Experimental Marine Biology and Ecology; 398(1-2): 1–8.

Hammerschlag N, Gallagher AJ, Lazarre DM, Slonim C. 2011. Range extension of the endangered great hammerhead shark Sphyrna mokarran in the Northwest Atlantic: Preliminary data and significance for conservation; Endangered Species Research, 13: 111–116.